The sex education I received was decent, by American standards.

When I was eight, my female peers and I were ushered to the music room, where we ate our boxed lunches on the floor and learned about the menstrual cycle. I shuddered at the thought of ever bleeding from “down there” and spent the next several years terrified that I would get my first period in public.

When I was twelve, my middle school health teacher projected grainy slides of STD-afflicted genitals and explained that pregnancy and childbirth would ruin your life. The class did, however, cover various forms of contraception and a very brief lesson on consent. When a classmate asked if sperm could, like, crawl up your leg, we all laughed at her question while secretly waiting to hear the answer.

When I was fifteen, and approaching a time in my life where comprehensive sexuality education might be especially useful, my otherwise progressive high school recommended an online health education course through Brigham Young University. So I learned about sexual health through a religious institution that prohibits its students from engaging in premarital sex and forbids any and all same-sex intimacy. Though the course materials briefly covered contraceptive methods, they clearly and repeatedly emphasized abstinence and completely excluded non-heterosexual relationships.

I supplemented that education with regular articles from Cosmopolitan, which taught me more about “how to please my man” than how to understand my body. It wasn’t until my junior year of college that I took–and later taught–a truly comprehensive, pleasure-based sex education course.

Yet compared to many young people across the United States and around the world, I was quite lucky. In 2011-2013, only 55 percent of young men and 60 percent of young women in the U.S. had received formal instruction on birth control methods. The percentage of American high schools teaching sex education has declined across a range of topics. And even when provided, sex ed is hardly comprehensive. As of 2015, fewer than six percent of LGBT students reported that their health classes included positive representations of LGBT-related topics.

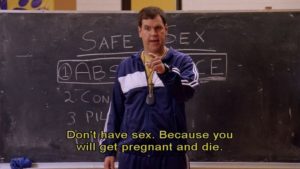

In the United States, sex education is highly variable. There is no federal mandate requiring school to teach sex ed, leaving individual states to regulate curriculum. In general, the nation’s sex education emphasizes abstinence and takes a cautionary tone. Some students learn nothing about sexual health, and some are provided only toxic misinformation.

But this isn’t the case around the globe. In the Netherlands, for example, all primary school students are required by law to receive some form of sexuality education. Though schools and teachers have some degree of autonomy in how they deliver the material, they must adhere to a core curriculum that includes sexual development, sexual diversity, and sexual assertiveness. “The underlying principle is straightforward,” writes Saskia de Melker for PBS. “Sexual development is a normal process that all young people experience, and they have the right to frank, trustworthy information on the subject.”

Dutch sexuality education begins as early as age four, when children receive lessons on relationships, appropriate touching, and intimacy. The curriculum expands to include age-appropriate topics and concepts. Seven-year-olds learn the proper names of different body parts and eight-year-olds discuss gender stereotypes. By the time they are 11, Dutch students should be able to discuss reproduction, safer sex, and sexual abuse.

Data suggest that the Dutch approach to sexuality education is incredibly effective. On average, teens in the Netherlands do not have sex at an earlier age than those in other European countries, and they tend to have positive first sexual experiences. Dutch teens are among the top users of the birth control pill, and nine out of ten used contraceptives the first time they had sexual intercourse. The Netherlands boasts one of the lowest rates of teen pregnancy in the world, as well as low rates of HIV and other STIs. While widely accessible contraception certainly contributes to this, a growing body of research suggests that starting comprehensive sexuality education at a young age helps avoid unintended pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections.

Clearly, the Dutch approach to sex education is highly effective. Centering love, empowerment, and respect in sexuality education curriculum, rather than fear, shame, and stigma, makes for a healthier and happier society. The Netherlands offers an excellent lesson in the positive power of comprehensive sexuality education. And in the United States, we have a lot to learn.

Interested in learning more about sex education around the world? Tune in next week for an overview of comprehensive sexuality education in Kenya!

– Anna Katz, Communications Intern