What is the function of the clitoris?

Before I began teaching comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) at WISER Girls’, a secondary school located in Muhuru Bay, Kenya, I never imagined that this would be the most frequently asked question. Especially among a class of female third-year high school students. When I was first asked, I gave a cursory – and yes, somewhat bashful – reply, explaining the clitoris as the “anatomical source of sexual pleasure in females.” But this answer did not satisfy the students, and they probed for more information. As we engaged in a discussion, I learned that many weren’t familiar with an external representation of the female genitalia – especially one with a “non-reproductive” function. As my answers became more justificatory about the significance of the clitoris, I realized that my attitudes about legitimized female sexuality had begun to leak into my responses. While I tried to remove any bias from my answers, I struggled with leaving my students with the impression that this structure is “non-essential” or associated with promiscuity- beliefs that have been integral to the justification of female genital cutting (FGC) across the globe.

This experience underscores the difficulties of teaching sexual and reproductive health (SRH). Seemingly innocuous anatomical questions elicit heavily personal- and culturally-constructed notions of sex and sexuality. It became clear that my understanding of reproductive anatomy, physiology, sexually-transmitted infections (STIs), and contraceptive methods would not be enough to be an effective CSE teacher. I also needed to understand the determinants that constructed students’ and societal SRH-related values and knowledge. In the next SRH session, I adapted an activity to unpack the layers of stigmatization and shame around female sexuality and reproduction and repackage them in a way that my students would feel empowered to make healthy decisions about their sexuality. We broached the topic of gender-based violence and FGC to highlight the importance of understanding anatomy and biological vulnerabilities faced by women across the world. A question as purportedly simple as “What is the function of the clitoris?” reinforced an important lesson about the influence of culture on SRH values and education: as much as we try, it’s impossible to separate and crucial to understand the influence of culture and contextual factors on SRH education.

CSE builds sexual self-efficacy, changes attitudes about gender norms, and strengthens communication, decision-making, and critical thinking. These facets of CSE are vitally important in Muhuru Bay, where young people constitute the largest proportion of people living with HIV/AIDS and nearly 22% of adolescent girls in Nyanza are pregnant or mothers (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics). In Muhuru Bay, earlier access to CSE and SRH could change health outcomes with lifelong effects. After my first experience in Muhuru Bay teaching in local primary schools and holding SRH sessions at church youth groups, I learned about the various ways CSE is disseminated in Muhuru and the potential barriers youth might face to accessing CSE. With so many barriers, and so many SRH-related challenges disproportionately impacting Muhuru youths compared to any other region in Kenya I wondered, how could youth access to CSE be supported?

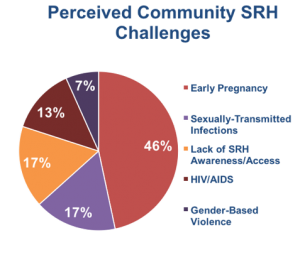

To help answer this question, I returned to Muhuru Bay in 2017 to work with WISER Girls’ to develop a peer-led adolescent SRH program that would help address the barriers to CSE. Rather than employing the old approach of directly teaching SRH to youth in the community, a more sustainable, culturally-grounded approach was utilized: secondary school students at WISER Girls’ would be trained to teach CSE at six different schools across Muhuru Bay. In my role as the facilitator of SRH training at WISER, I attempted to bridge the divide between the “facts” of SRH, like anatomy and STIs, and the way that culture influences health and health education. Through specific activities, the WISER girls’ debunked the myths and stigma around SRH in Muhuru and found ways to relay that information to youth by employing engaging activities. Our unpacking of cultural values – in the case of the clitoris – served as a practical example of how to approach this type of question when the girls themselves would teach their own primary school students.  After the girls identified community SRH challenges they thought were most important, we developed a curriculum that ranged from basic SRH concepts i.e. anatomy/physiology to larger concepts such as gender roles, sexual decision-making, and dispelling stigma associated with STIs and early pregnancy.

After the girls identified community SRH challenges they thought were most important, we developed a curriculum that ranged from basic SRH concepts i.e. anatomy/physiology to larger concepts such as gender roles, sexual decision-making, and dispelling stigma associated with STIs and early pregnancy.

Across six different primary schools, the WISER girls delivered weekly CSE to almost 300 adolescents enrolled in the program. As I observed the sessions, I saw how the WISER girls fluidly switched between Dhuluo and English, able to effectively answer questions across language barriers and with a unique cultural understanding that I could not even begin to match. I saw youth look up to the WISER girls as mentors and beloved members of their community as they sought to keep them after the sessions. Since the girls are embedded in the community, this model may be a more sustainable way to deliver CSE to youth and empower young female leaders with the ability to effect positive change in their communities. Despite the end of the pilot program over the summer, I have no doubt that the WISER girls will continue to mentor young people in the community.

In addition to addressing all five identified barriers to CSE, these peer educators felt empowered by their own role in effecting positive change in their community. One of them told me,

“It improved [my self-confidence]. Because when I was teaching those people, it was my first time teaching. I have never taught anyone before, like even in church. Now I feel like I can teach, like I can be a teacher!”

Ultimately, one of the goals of teaching is to inspire students; however, it is easy to instead end up being inspired by your students. In the same way that I was inspired by the incredible work the WISER girls did in their community for this program, they were inspired by their students and the significance of their work. Despite the difficulties of teaching a subject like SRH, the girls rose to the challenge. They showed not only me, but the entire community the capacity of young people to improve SRH and empower their peers.

Blog post by: Pranalee Patel