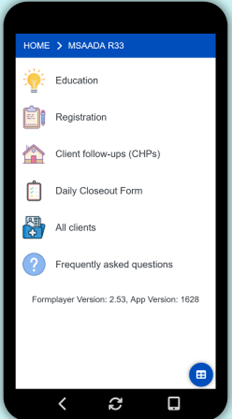

When I first inquired into the Center for Global Reproductive Health’s cervical cancer screening and prevention research, I wasn’t sure where I should focus my efforts. After all, the center manages an impressive array of projects in Kisumu. First, there’s the ongoing R33 trial, an RCT evaluating the impact of the mSaada mobile app on HPV testing and treatment uptake. Then there’s Elimisha, a model of education and screening designed to measure and mitigate HPV and cervical cancer stigma. The Kenya-based team is also responsible for training Community Health Promoters (CHPs) and monitoring the supply needs of 12 dispensaries and hospitals across Siaya County. Each endeavor requires a set of carefully crafted tools for implementation, data collection, and analysis. Thus, even before we landed in Kisumu, our SRT team knew that we were entering a network of projects bursting with experience and hard-won lessons in global health implementation.

Our newly arrived team celebrated our first full day in Kisumu with Dr. Huchko.

Our team of three was tasked with a clear goal: to aid the implementation of the mSaada R33 trial, from training CHPs to iteratively testing the app’s features. We are facilitating the introduction of HPV testing into 6 health facilities that will employ mSaada (intervention sites) and 6 locations that will utilize paper documentation tools instead (control sites). Throughout our first month in the field, however, we’ve discovered that this objective requires an eye for broader health system challenges, including those that once appeared beyond the defined scope of the R33.

Under the mentorship of Dr. Thao Nguyen and Assistant Data Manager Evans Otieno, we tested many client scenarios in mSaada to ensure the app can reliably guide CHPs through the screening process.

Our first few weeks have certainly brought tasks proximal to the screening process itself. For instance, we’ve tested several iterations of the app’s registration forms and crafted teaching tools and role plays to enhance CHPs’ confidence in counseling women about HPV.

But we’ve also had numerous explorations into unfamiliar territory – issues just as crucial to the R33’s success but not at the forefront of the study design. Chief among them is the challenge of sanitary pad access. After testing positive for HPV, women are referred for thermoablation, a simple procedure that treats precancerous cervical lesions but can sometimes cause spotting and bleeding. Through conversations with providers, nurses, and community health assistants (CHAs), we’ve learned that several facilities are ill-equipped to offer sanitary pads to all thermoablation patients. Supplying enough quality pads to each patient who undergoes thermoablation is key to the R33’s relationship with its partners and clients. It can demonstrate our desire for the best possible patient experience and our commitment to supporting the clinics hosting our intervention. Pad provision is not explicitly noted in the study’s workflow but is nonetheless a vital component of cervical cancer screening and prevention.

We held our first CHP training and mentorship at Lidha Dispensary. Lidha is where we first inquired into sanitary pad supply challenges.

The next step in our aim to alleviate these pad supply challenges is to ask the right questions. We will document how each of the 12 facilities manages pad needs and stocking, searching for an understanding of these supply challenges in the context of period poverty throughout Siaya County. Through collaborating with our expert study coordinators and research assistants, we hope to be a part of a sustainable solution.

I’m most grateful for my time in the field so far because of the stirring action it has inspired in our team. After engaging academically with both cervical cancer burden and pad inaccessibility from classrooms, witnessing their intersection and tangible human impacts in western Kenya has been the most galvanizing experience I’ve had as a student of global reproductive health.